LLM Architecture Series – Bonus Lesson. In earlier lessons you saw how tokens become vectors. This article goes deeper into what those vectors mean and how simple arithmetic on them can reveal structure in concepts.

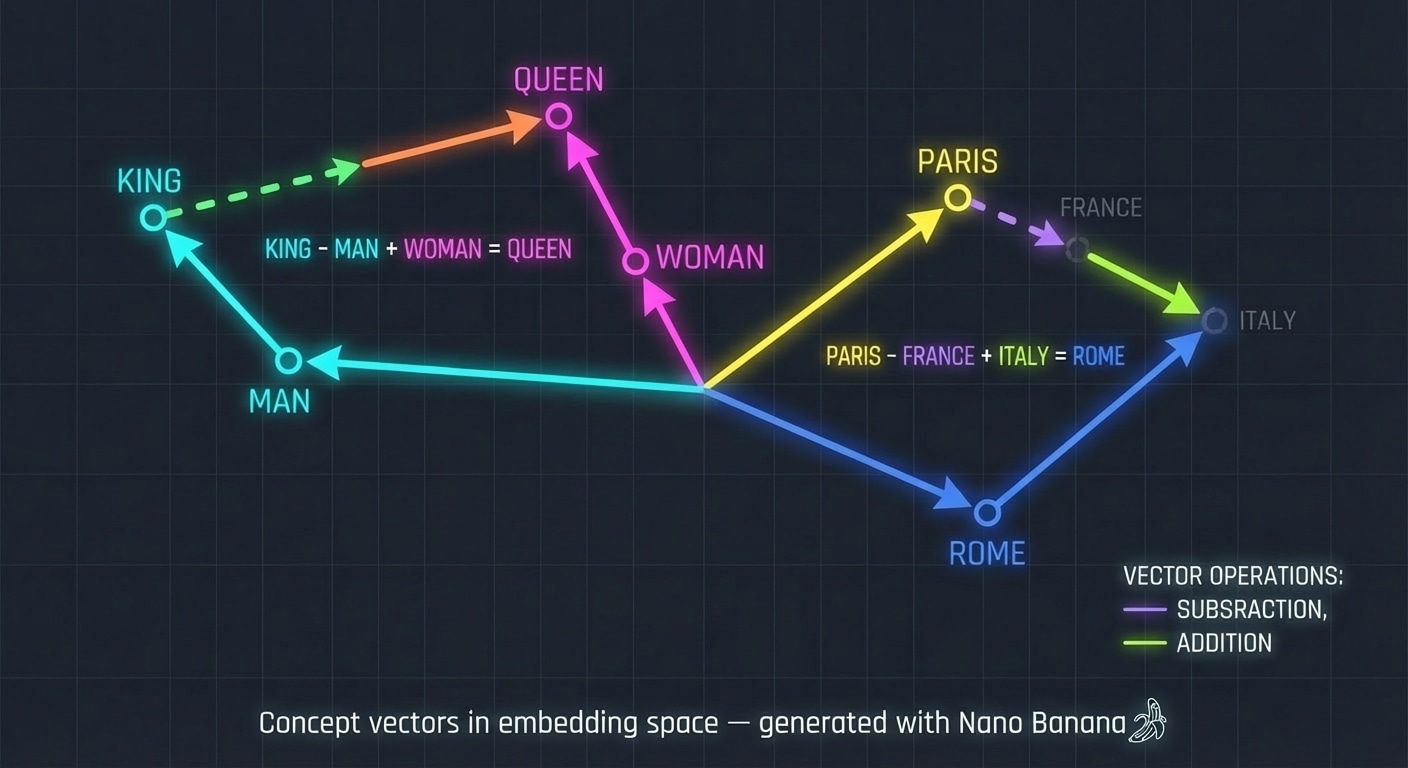

Concept vectors in embedding space — generated with Nano Banana.

From words to points in space

When we embed tokens into a vector space, we assign each token a coordinate in a high dimensional space. Tokens that appear in similar contexts end up near each other, even if they never occur in exactly the same sentence.

You can imagine a huge cloud of points where adjectives cluster together, city names form another cluster, and verbs live in yet another region.

Directions as concepts

The magic of vector spaces is that differences between points often correspond to differences in meaning. A direction in this space can capture a concept like gender, tense, or even formality.

For example, in many trained models there is a direction that roughly turns a singular noun into its plural form. Moving along that direction can transform cat into something closer to cats and car into something closer to cars.

Analogy as vector arithmetic

A classic way to demonstrate this structure is with analogies of the form:

vector(king) – vector(man) + vector(woman) → vector close to queen

This is not a hard rule, but in many embedding spaces it approximately holds. The “royalty” concept and the “gender” concept appear as directions that can be combined.

Other examples often emerge:

- vector(scientist) – vector(lab) + vector(hospital) lands near words like doctor.

- vector(Paris) – vector(France) + vector(Italy) lands near Rome.

- vector(jazz) – vector(club) + vector(orchestra) moves you toward terms like classical or symphony.

These are signs that the model has learned reusable abstract relationships, not just surface statistics.

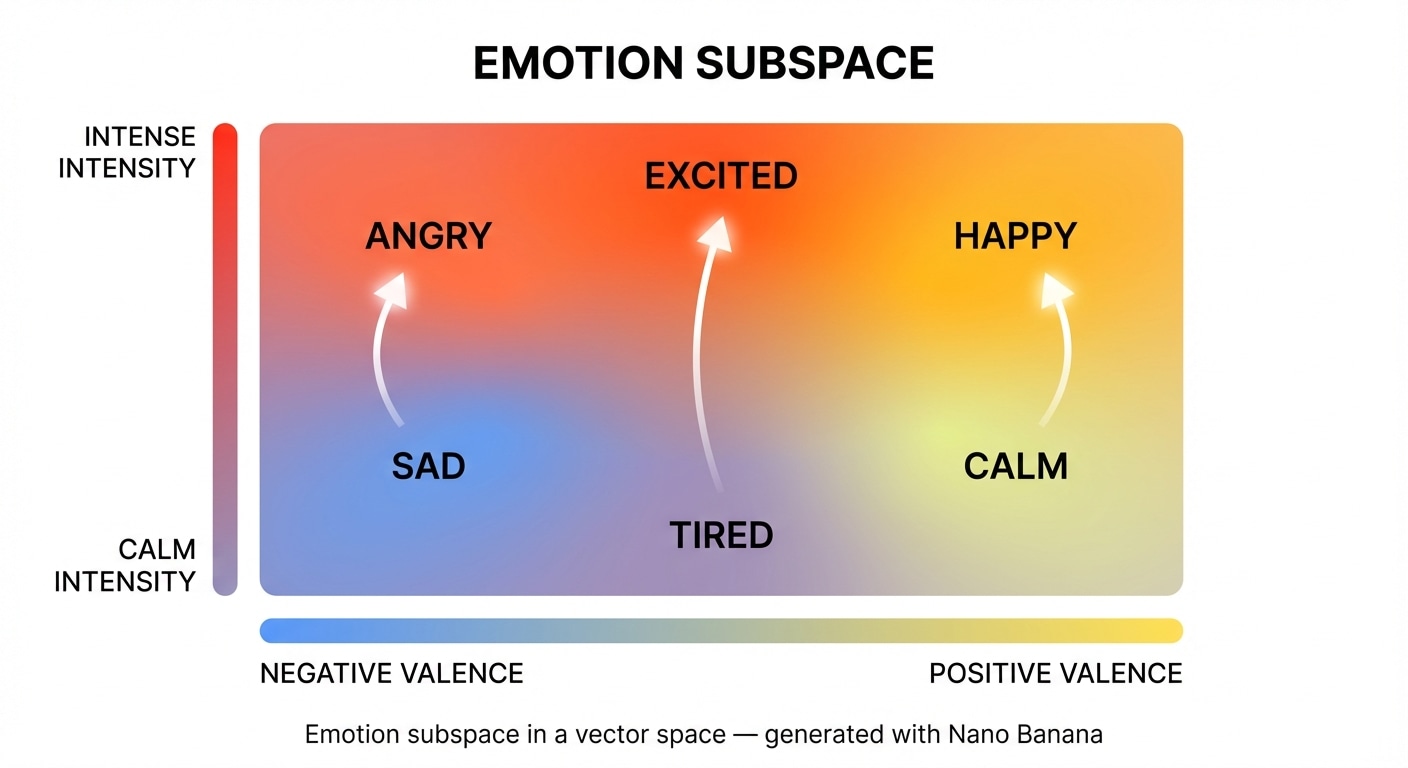

Emotion subspace in a vector space — generated with Nano Banana.

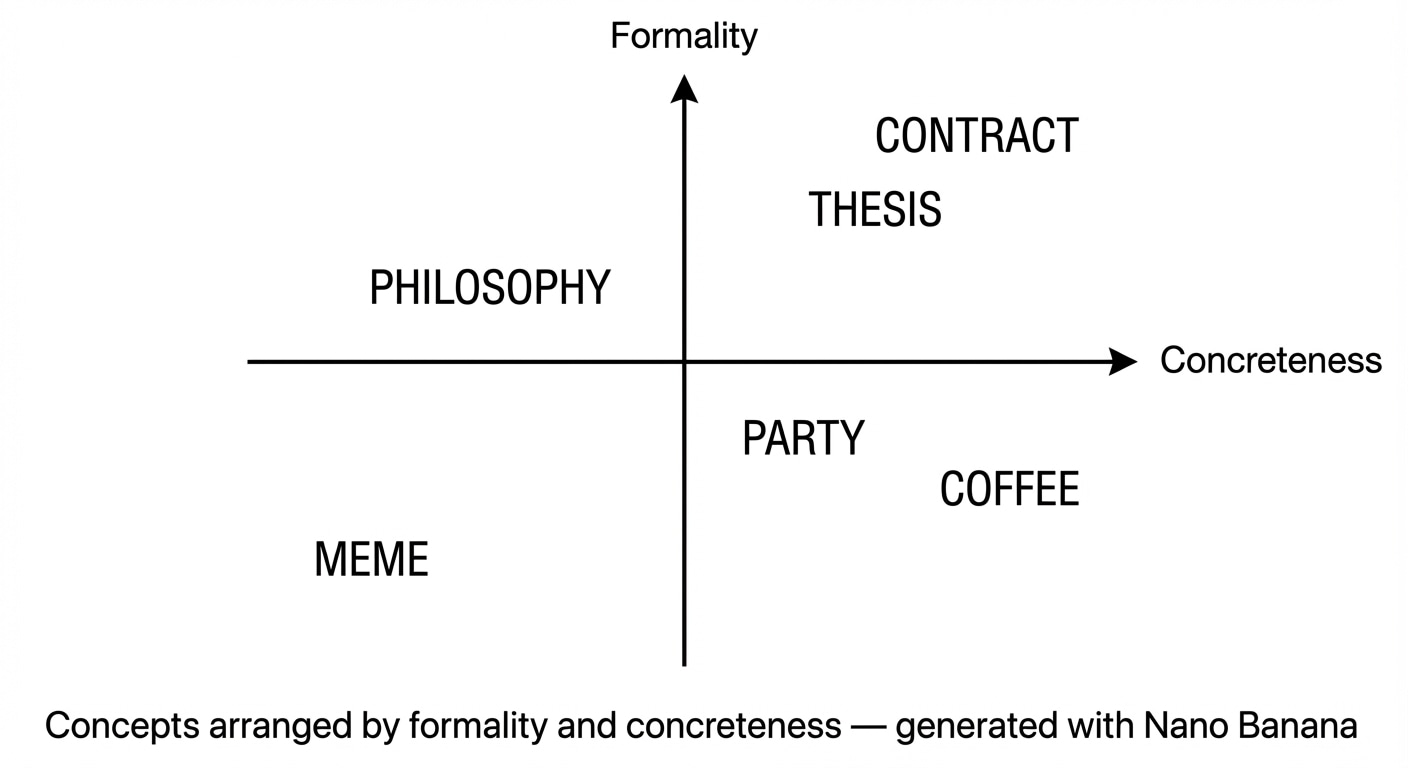

Geometric intuition

It helps to pretend that the embedding space is only two or three dimensions, even though real models use hundreds or thousands. You can then picture:

- One axis for formality (casual to formal).

- One axis for sentiment (negative to positive).

- One axis for concreteness (abstract idea to physical object).

A word like party might live in the casual, positive, concrete quadrant, while philosophy lives in the abstract, neutral, somewhat formal region.

Concepts arranged by formality and concreteness — generated with Nano Banana.

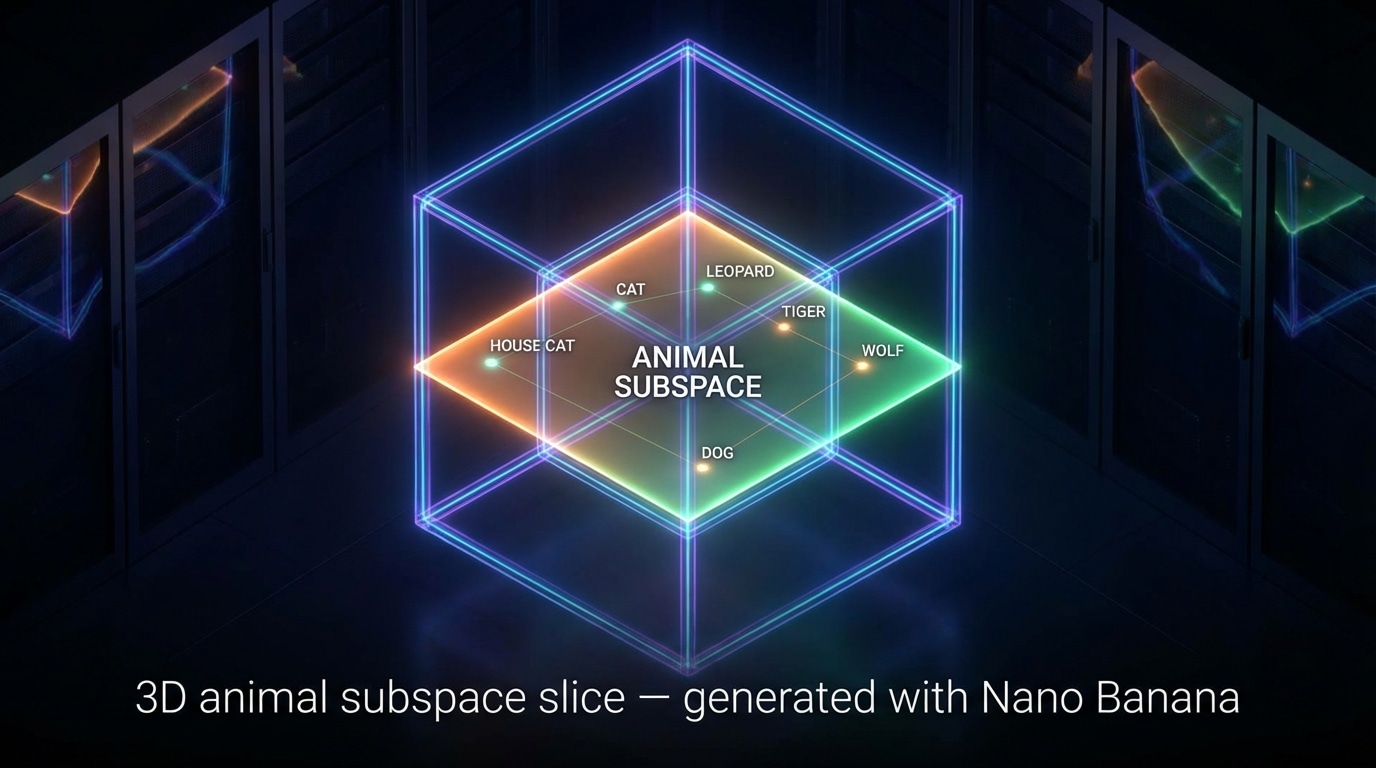

Concept subspaces

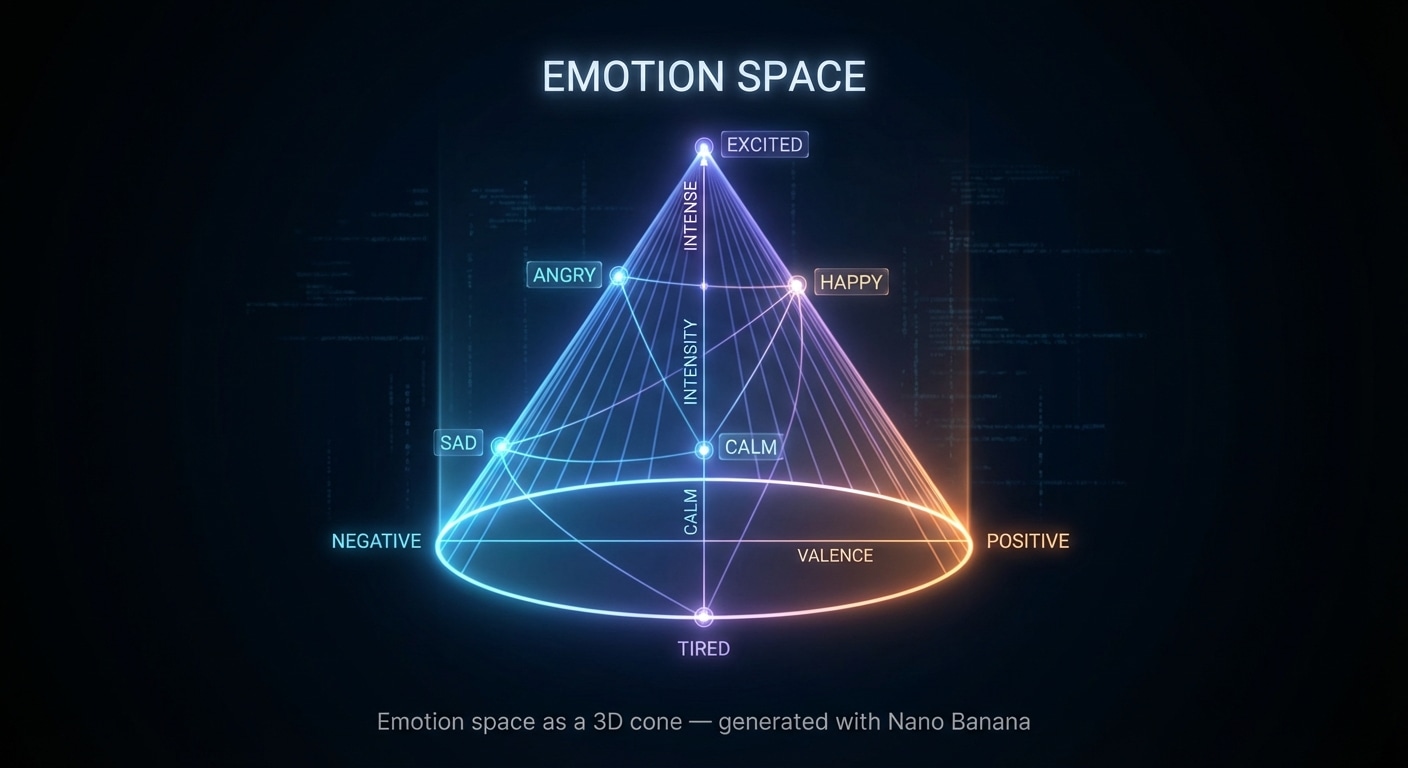

Often, we can find a lower dimensional subspace that captures a particular family of concepts. For example, emotions such as happy, sad, angry, calm may roughly lie on a plane where one direction measures intensity and another measures valence (positive versus negative).

Moving within that subspace lets the model smoothly change tone while keeping the rest of the meaning similar.

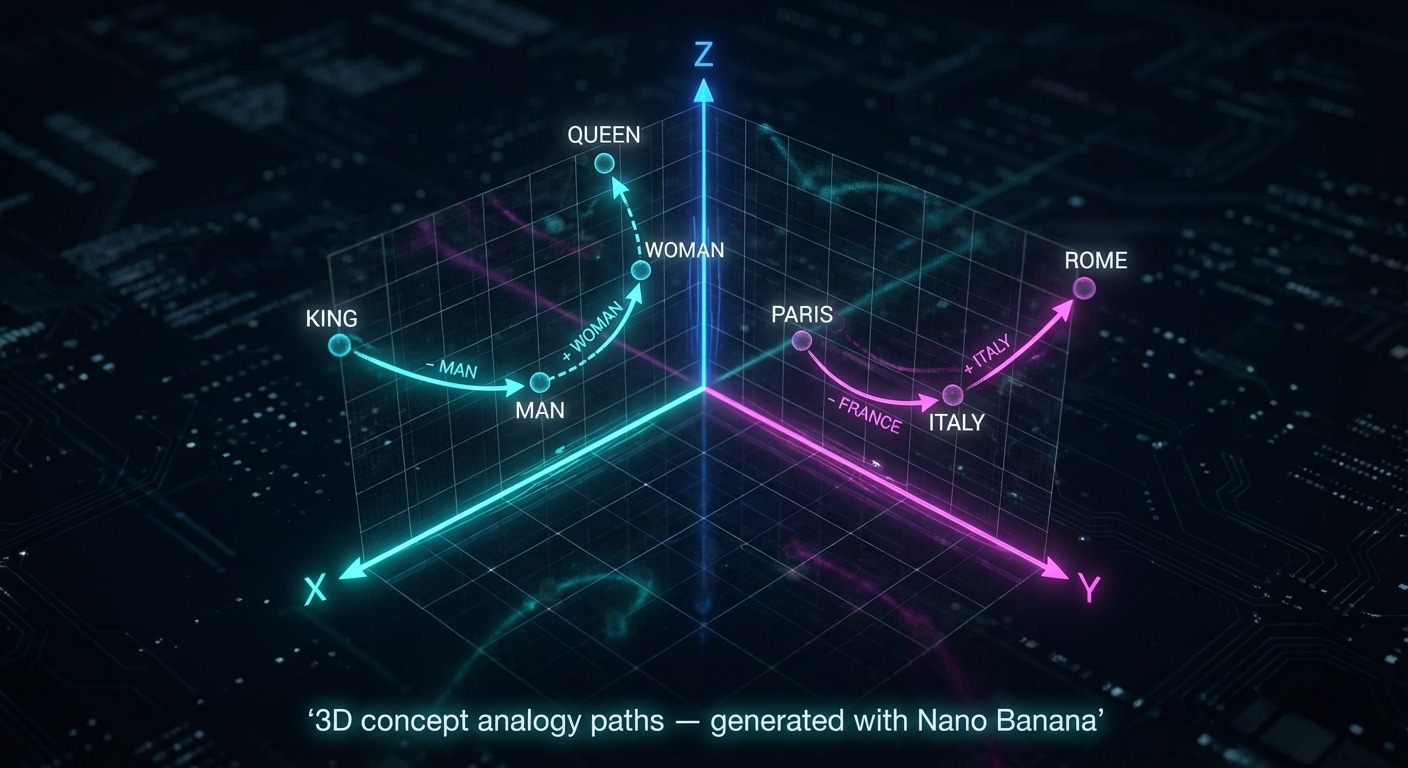

3D views of vector spaces

To complement the earlier 2D diagrams, these 3D style views show the same ideas of analogy, emotion, and concept subspaces from a different angle.

3D concept analogy paths — generated with Nano Banana.

Emotion space as a 3D cone — generated with Nano Banana.

3D animal subspace slice — generated with Nano Banana.

Why this matters for LLM behavior

Because concepts are represented geometrically, operations like interpolation, extrapolation, and analogy fall out naturally:

- Interpolating between two embeddings can create a meaning that blends both concepts.

- Extrapolating along a direction can exaggerate a property, such as making text more formal, more emotional, or more technical.

- Analogy arithmetic gives the model a way to move between related concepts even when it has never seen the exact example before.

Limitations and caveats

Vector arithmetic analogies are illustrative but imperfect:

- They work best on well represented, unambiguous concepts.

- They may fail for rare words, culturally loaded terms, or multi word expressions.

- The space is shaped by the training data, so biases and gaps in that data are reflected in the geometry.

Still, they provide a powerful mental model for how modern language models encode and manipulate meaning.

Connecting back to the series

In earlier lessons you saw how tokens become embeddings and how attention moves information around. This article shows that these embeddings are not arbitrary numbers, but points in a structured space where directions correspond to meaningful changes.

When you next look at attention patterns or feed forward activations, you can imagine them as operations that bend and rotate these vectors to emphasize the concepts that matter for the current prediction.

Where to go next

If you are following the LLM Architecture Series in order, you can now revisit the embedding and attention lessons with this geometric picture in mind. Try to imagine how a single token flows through the model, moving through vector space as it interacts with other tokens.

From here, you might also explore visualization tools that project high dimensional embeddings into two or three dimensions, or experiment with simple word vector models to build your own intuition.

This article is part of the LLM Architecture Series on SudoAll. You can find the full index on the LLM Architecture Series page.